A conversation about gender and transition

Our starting point should be chosen by observing that God gave us two ears, but only one mouth

The swirl of controversy surrounding gender transition and our children has stirred again, with The Free Press featuring an explosive whistleblower from a Missouri pediatric clinic. We are likely to see Congressional hearings in the newly elected House of Representatives.

Personally, I believe both race and gender are being exploited by Marxism as it breathes its last breaths as a viable ideology. As an economic theory it failed to gain the support of the masses in Soviet Russia. It then morphed into a cultural ideology and sought - and failed - to gain ascendancy via the U.S. Courts. Marxism has now turned its energies toward hijacking teachers’ unions and seeking ascendancy in our elementary schools. The effort boils down to separating the formation of our children’s identities from home and family. It is not a new tactic or goal - just pursued by different means.

I worry because there are very real, lived human experiences that are being drowned out. And along with them, we as Christians are losing an opportunity to deepen our spirituality and understanding of what the life of Jesus Christ might teach us in this moment. My friendships with people who are genuinely struggling with gender dysphoria/dysmorphia (there are thoughtful discussions about which is the more accurate clinical term) have not “changed my mind,” per se, about what I call the “heterosexual complement of nature.” But they have opened my heart. And what I mean by that is specific - we have to choose a starting point for this conversation about gender. And that starting point will either be our Natural Law arguments or the real, lived experiences of our neighbors.

Why I believe we have to choose our starting point

I have chosen to listen first. Here is why:

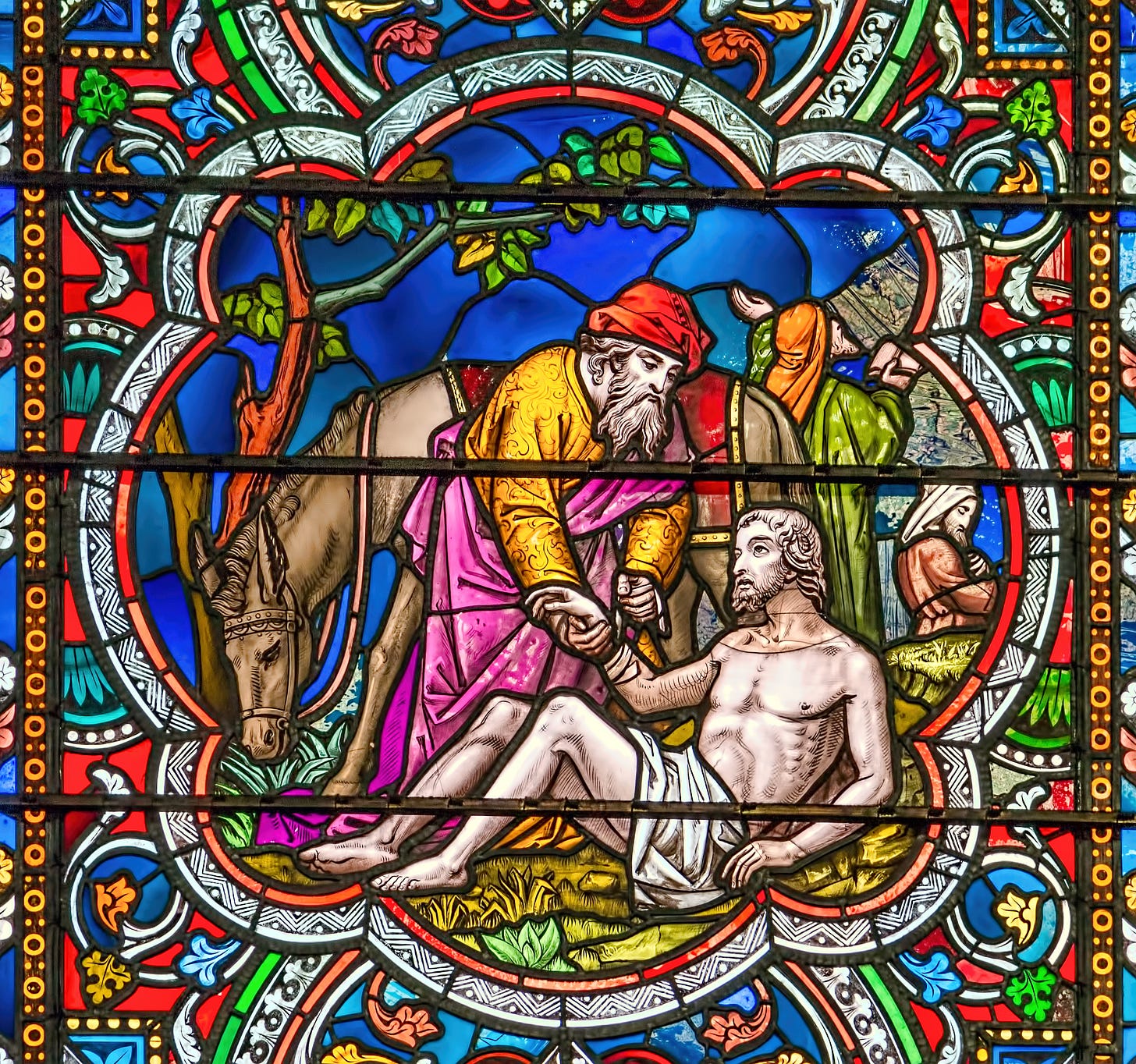

The Parable of the Good Samaritan is brought to us by St. Luke - the author of the Gospel (good news) that the New Testament presents as “according to” Luke. There are four such Gospels - the first four books of the New Testament.

I have reflected elsewhere about how getting older changes one’s perspectives on how important things are; I find myself valuing friendships more as I age. (I placed a link to this reflection, instead of pronouns, in my email signature and the post is now at the top of the favorites list in this blog.)

I have always been one who tended toward ideas - weighing arguments for and against. I am convinced it has been the amazing example of my older son that has taught me to value stories. He is everything I wish I had been at his age. And it is because he does not worry so much about who is right or wrong that he is able to easily enter into his friends’ stories. I can only pine for a past life where I might have made friends as easily as he does.

But I am learning... even in my old age. My academic background (M.A. in Theology and M.Div.) enables me to approach the Gospels with questions about how stories are told, instead of just about ancient languages and their grammar. My life experience has blessed me with friendships in the LGBT community. If my faith is only about the language and grammar of the Bible, I am held hostage by legalism. If my faith is only about human experience, I am held hostage by relativism.

Please be patient with me as I navigate between these rocky shores.

The Parable of the Good Samaritan is a not just a story told by Jesus; it is a story told by St. Luke of Jesus telling a story in response to a challenge. So let’s back up and take this all in. I am going to use a translation known as the “New King James Version” (NKJV). I use this version because it is more literal while being informed by more recent discoveries (of ancient texts) than the older King James Version. This is from Luke’s Gospel, Chapter 10. The numbers refer to the “verses.” (These were added by translators and are not part of the ancient copies.)

25 And behold, a certain lawyer stood up and tested Him, saying, “Teacher, what shall I do to inherit eternal life?”

26 He said to him, “What is written in the law? What is your reading of it?”

27 So he answered and said, “‘You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, with all your soul, with all your strength, and with all your mind,’ and ‘your neighbor as yourself.’”

28 And He said to him, “You have answered rightly; do this and you will live.”

If we are reading this with our attention to storytelling rather than grammar, what should stand out is how the story tells us something about the lawyer’s intentions: he ‘tested’ Jesus. The lawyer wanted to see how Jesus would answer. If I might be a bit cheeky, I would quote Jesus as responding: “Well, you’re the lawyer... you tell me.”

And the story tells us quite plainly: The lawyer was right. But apparently being right wasn’t enough.

29 But he, wanting to justify himself, said to Jesus, “And who is my neighbor?”

And St. Luke does it again: He started by giving us this cue into the inner life of the lawyer by saying he “stood up and tested [Jesus].” Here (in verse 29), St. Luke says he is “wanting to justify himself.” If we look away from language and grammar to storytelling, we can see that St. Luke is assuming a “third person omniscient” perspective in the story. St. Luke is saying something very important about the lawyer as a character in this story: His intentions and motives are inward; he seeks to ‘test’ Jesus and otherwise ‘justify’ himself (in the view of???).

It is in the actions and dialog of the Parable that we see a contrast:

30 Then Jesus answered and said: “A certain man went down from Jerusalem to Jericho, and fell among thieves, who stripped him of his clothing, wounded him, and departed, leaving him half dead.

31 Now by chance a certain priest came down that road. And when he saw him, he passed by on the other side.

32 Likewise a Levite, when he arrived at the place, came and looked, and passed by on the other side.

33 But a certain Samaritan, as he journeyed, came where he was. And when he saw him, he had compassion.

34 So he went to him and bandaged his wounds, pouring on oil and wine; and he set him on his own animal, brought him to an inn, and took care of him.

35 On the next day, when he departed, he took out two denarii, gave them to the innkeeper, and said to him, ‘Take care of him; and whatever more you spend, when I come again, I will repay you.’”

Let us not be distracted from the text by speculation

Jesus’ story also has characters: the priest, the Levite, and the Samaritan. Christian commentators have speculated on why the priest and Levite act as they do. But it is critical to note that there is nothing in the story that tells us about their “inner life.” Speculating away from the text of the story distracts us from what is actually there: The Samaritan “had compassion.” And he acted on it.

The intentions and motives of the Samaritan are outward: if there are concerns about being ceremonially unclean by coming into contact with an apparently dead body, or with bodily fluids, the Samaritan’s example reveals a choice: follow the “rules” or act with compassion. The Samaritan can’t do both; he must choose.

36 So which of these three do you think was neighbor to him who fell among the thieves?”

37 And he said, “He who showed mercy on him.” Then Jesus said to him, “Go and do likewise.”

The expert in the law was seeking the hope of eternal life in his argument; he didn't find it there. It was only to be found in the compassion of the Samaritan and in the command of the Lord.

We are nothing if not experts in our Natural Law arguments about the heterosexual complement of nature. But there they are - neighbors created in the image of God with real, living stories of crushing isolation and loneliness. It’s not that our beliefs are wrong or unimportant. If Jesus were among us He might say as He did to the expert in the law - “You have answered rightly…”

What we must ask ourselves is whether we think the hope of eternal life is to be found in being right. And if so, why do we believe that in light of this Parable?

These conversations are so pressing right now. But they can only start at one of two places: Either our expert arguments or our neighbors’ stories. The Samaritan had to choose. We do as well. And our Lord laid out the right choice for us in no uncertain terms:

“Then Jesus said to him, ‘Go and do likewise.’”