Artificial Intelligence: What it Is, and What it Isn't (Hint: It's not a 'race')

When mixing metaphors becomes necessary for good thinking

[TL;DR - The more I read about AI the more convinced I become that we have gone off the “deep end” when it comes to expecting technical precision in ordinary conversation. On Thomas Paine’s Blog I purposefully expose myself to ridicule from the “specialists” because I honestly believe that learning requires prior frames of reference, and those frames should not have to conform to the expectations of ‘experts’. On no other subject does this seem more apparent than AI. We simply MUST have a prior frame of reference, even if when forming it we end up being less than accurate. The following article makes some necessary compromises to explain how AI forces computer science and philosophy into a necessary intersection.]

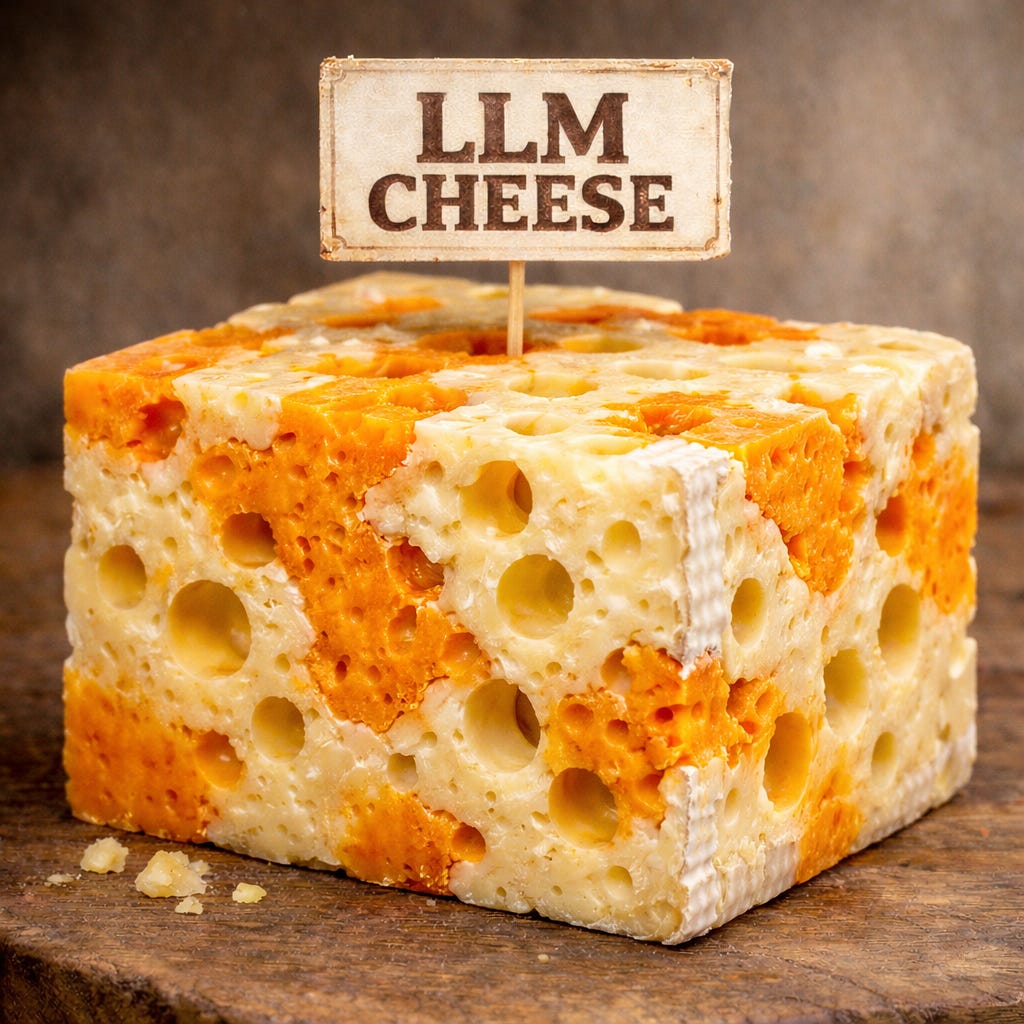

If you love cheese - and even if you don’t - you can probably imagine holding a knife as you slice through a block. It takes some elbow grease if its hard cheddar. It’s like a “hot knife through butter” with soft brie. And if you’re cutting into Swiss, you expect those empty pockets from the CO₂ that develops during fermentation.

I’ll explain more below, but this is what a Large Language Model is like. The metaphor (I know… it’s really a simile… humor me, OK?) isn’t quite exact because the block of cheese has six faces and the cheese is on or inside those faces. LLMs aren’t quite like this in the on, inside, or outside sense. But I’m going to use the metaphor anyway because there are some things about cheese that can really help the average person understand what AI is, what it isn’t, and why it all matters.

Cheddar, Brie, and ‘Swiss Pockets’

When LLMs train on a large set of texts, words and phrases are transformed into ‘embeddings’ or ‘vectors.’ If you can imagine a mental space containing points that shift relative to one another based on how they pair with other points, you have the beginnings of a frame of reference. From there, it is natural to assume something like a 3D cube,1 (ergo the block of cheese). Roughly speaking, things that are opposite or unlike each other will appear far apart within the cube.2 The “points” for things that are similar or like each other will be closer to each other.

When the “textual corpora” (specialty language for the whole body of texts fed to the model to be transformed into embeddings) contains a lot of material on a specific subject, the embeddings will pack tightly together in roughly the same “space” within the cube. Where the subject matter is sparsely covered in the textual corpora, the embeddings will be less dense in a given space. And in some areas the embeddings are so sparse as to be “epistemically insignificant.” (There we go again. Specialty language. Hang in there.)

The relatively dense vs. sparse distribution of the embeddings transformed from text is why I worked with ChatGPT to get the image of this block of cheese just right. (It took quite a few prompt iterations.) Recalling the effort needed to slice hard cheddar vice soft brie, the areas of an LLM where the embeddings are densely packed are the orange cheddar in the block of cheese. When the embeddings are more sparsely distributed, we have the soft brie.

And then we have the ‘Swiss Pockets’.

It is not quite accurate to say there is nothing there. Even in an actual block of Swiss, there is the CO₂ that created the pocket. The problem is the underlying textual corpora contains so little data in this “area” that the LLM can only approximate where the embeddings from that text should land.

It is very important to understand what does and does not happen when you run into a Swiss pocket.

The LLM does not “make things up.” The term “hallucinate” is actually one of the worst possible words we can use because it sounds like the LLM is “seeing something” that isn’t really there. I think it is safe to say that - mathematically - this is absolutely NOT what is happening.

The LLM does not “guess.” It is statistically analyzing the patterns in your prompt. Then, similar to how an infrared (IR) camera can be tuned to “light up” things based on temperature, areas in the model are “lit up” based on the patterns in your prompt. The model then infers from those areas how your prompt’s patterns usually complete themselves. It generates its response accordingly.

Swiss Pockets as ‘Epistemic Voids’

So, what, exactly, is happening in and around these pockets? This is where computer science and philosophy begin to intersect. We will have to start moving back and forth between the two somewhat. We’ll start with philosophy.

Classically, the study of philosophy breaks out into ‘ontology’ and ‘epistemology’. Both are crucial to understanding the promise - but perhaps much more importantly - the limitations of AI. Briefly,3 ontology inquires into reality as it actually is (i.e., what it means to “be”). Epistemology concerns itself with how we come to approximate reality, and what justifies calling that approximation knowledge.

We can approximate reality visually (with graphics) as well as textually (with language). We can create a fictional “reality” for our entertainment via 3D animation. It turns out that human languages model “reality” in all but exactly the same “3D” way. AI really is “the geometry of human language.”4 By recognizing at the outset that language merely approximates reality, we set ourselves up to appreciate the philosophical limits of AI. Epistemology in this context then becomes an inquiry into when, how, and why the outputs of an LLM can be justified as knowledge.

So, now let’s swing from philosophy to computers.

The reason I find the Swiss cheese pocket a compelling metaphor is because it describes spaces in the geometry of the LLM where embeddings are only provisionally located. There are embeddings there, but they have been created from very little data. Locating the embedding somewhere in the pocket is statistically justifiable, even if its specific location is not well-grounded - again, for lack of adequate underlying data.

Ultimately, your prompt is going to start a pattern and the LLM is going to complete the pattern. If your prompt pattern “lights up” an area with pockets of “poorly grounded” embeddings, the LLM will complete the pattern by making the best inferences possible from those poorly grounded embeddings. Or the LLM will look to a cheddar or brie area nearest to the pocket and use those areas to infer the completion of the pattern.

The problem here is that the LLM output will “sound knowledgeable” even though the answer is not well-grounded; the LLM does not really ‘know’ anything.

Data, Information, Knowledge, Wisdom (DIKW)

Here on the computer science side of the intersection between philosophy and computers is a discipline called “knowledge management.” This starts with data being gathered from diverse sources. An “ETL Engineer” (ETL stands for Extract/Transform/Load) writes code to extract this disparate data, transform it into a common format, and then load it to a computer system. That system will “contextualize” the data. The textbook definition of the word “information” is “data-in-context-with-data.”

Then - again to oversimplify - math is done on the information to generate knowledge. That knowledge then becomes the basis for (hopefully) good decision-making - wisdom. That math - inference - is what the LLM is doing when it completes the patterns started in your prompt. And that is all the LLM is doing.

[UPDATE: 1/7/2026: I changed the paragraph below to avoid the implication that an LLM can “assume” something. It is us as users that “assume” things based on the fluency of the output.]

An LLM does not “know” anything. All it does is infer what comes next. Because the result appears fluent and natural, we assume what is stated to be true - even if the inferences are grounded with little to no actual data. As such, the LLM cannot determine for us whether its inferences justify calling its output ‘knowledge’.

To use another metaphor: When we have a deep “reservoir” of reliable data, we can produce dense, robust information. When we do math on this robust information, we can produce stable knowledge. On the other hand, where we have a shallow reservoir of reliable data, we can only have sparse information. We can do our math and produce knowledge - but we will be limited to volatile knowledge. In other words, it is highly likely this knowledge will change as it becomes more stable as the reservoir of reliable data deepens over time.

As for wisdom? Well, that should be pretty clear: We cannot reasonably expect wisdom from volatile knowledge.

With AI, we are geometrically modeling language in a boundless 3D space just like computer animation.5 If we are playing a computer game, being in the “cheddar” is like being in a part of the game crowded with lots of objects. Collisions are happening all the time and there are only a few ways you can actually move. In an LLM, that “crowding” limits the possible ways the LLM can complete the pattern you start with your prompt. Those limits are created by the volume of underlying data, so the LLM completes the pattern in predictable, tightly constrained ways.

The problem we face is that the LLM is designed to dynamically infer from our prompt a contextualization of embeddings in the model to create information. It will then infer the completion of the patterns we started. That completion will be presented to us in natural language as if it were knowledge. To the extent that the embeddings that make up the information come from densely packed cheddar regions transformed from reliable data, the LLM response presents a strongly inferred (meaning tightly constrained by lots of reliable data) completion of the pattern we started with our prompt.

Stressing this again: The LLM does the complex geometry of language for us: It can return to us strong inferences tightly constrained by the available information. It can also sound unreasonably confident in the absence of adequate information. Our task is to figure out what this implies for intelligence and knowledge.

‘Epistemic Optimization’

Once we get to a point where we understand epistemology as how we come to know things, and we appreciate how language is one way we represent what we know, then we can begin to appreciate how LLMs draw computer science into philosophy, and vice versa. We are faced with an a priori:6 We can no longer speak of computers without the conversation leaking into philosophy. Nor can we speak of coming to know things without that conversation leaking into computer science. In practice, we might express these constraints by saying that “Artificial Intelligence” is neither artificial, nor is it intelligent.

Computer science has proven that human language maps our understanding of reality in 3D geometric space much like we do with computer graphics. There is nothing artificial about the massive textual corpora humans have created to represent our understanding of reality - and the subset of that corpora from which an LLM is trained. There is nothing artificial about the complex statistics and data science that is being applied to this textual corpora to build out an LLM of geometric embeddings. There is nothing artificial about the starting patterns we provide in our prompts. There is nothing artificial about the statistical inferences which join the patterns in our prompts to patterns in the embeddings. There is nothing artificial about the best inference as to how the starting pattern most likely completes.

It has been said that if the only tool you have is a hammer, every problem looks like a nail. Alan Turing (1912 - 1954) might be considered the father of modern computing. He famously asked whether machines could ‘think’. He proposed the “Turing test” - whether a machine could perform in conversation in a way indistinguishable from a human. We might say his “Turing machine” (the forerunner of the computer) was his hammer and ‘thinking’ itself became his nail. By collapsing the idea of thinking and intelligence like this, he left us vulnerable to the mimesis of intelligence.

Mimesis is a term from philosophy that roughly describes our ability to imitate things. For Plato it was problematic and moves us further away from truth. For Aristotle it was a natural part of how we interact with the world around us and as such is essential to learning. There may be no contrast in classical philosophy more important to the discussion about the place of AI in our modern world. But to simplify: If a masterful impersonator can fool everyone into thinking they are the person being impersonated,7 that does not make them that person - it just means they are a masterful impersonator.

In software engineering, an “interface” defines how the program accesses and operates underlying data. If we might provisionally define “intelligence” as the way humans construct language as an “interface” between human thinking and reality, then all we have done with LLMs is normalize and optimize the interface across all domains of knowledge - epistemic optimization. We still have to judge for ourselves whether or not - along with why or why not - the output qualifies as knowledge.

Why this matters

There is something else “AI” is not. It is not a “race.”

In October 1957 American society was paralyzed with the fear that the U.S. was losing - or had lost - the “space race” to the Soviet Union. Sputnik orbited the globe, and could be seen traversing the night sky. President Kennedy later called the country to go to the moon, and in 1969 we did. That “one giant leap for mankind” felt like we had gotten our footing back. At least we won the race to the moon.

AI is not like this. The process of transforming text to spatial embeddings was discovered by a team working for Google at the time. If that is the finish line - well, we won already.

Since we have seen that LLMs model language in 3D geometric space like the mathematics used in graphics, it is not surprising that computer graphics cards (GPUs - or Graphics Processing Units) proved to be the best hardware/chip model for LLM operations. The challenge now is how to optimize the chip design to do the huge mathematical lifting using the least energy. This is not likely to “speed up” the LLMs, though, but to allow them to absorb ever larger amounts of training data, covering larger areas of knowledge with ever more densely packed embeddings.

But, as we have discussed above, this will only be as useful as the training data is reliable. We have discussed how LLMs generate text to complete a pattern started in the prompt. We have pointed out that completion can depend on ‘pockets’ in the LLM where the embeddings are provisionally located based on scarce data. If we explode this to the generation of whole papers that take the form of academic research, but do not represent actual research, we will learn a hard lesson - that more is not always better. Being able to transform ever larger volumes of text may only make it more likely LLMs develop densely packed embeddings from previously AI-generated texts - that were originally based on embeddings in the soft brie or the Swiss pockets.

But what about China?

Indeed, what about them?

What if China scales these systems faster, regardless of quality, and gains an advantage? The concern is understandable, but it rests on a mistaken assumption - that speed and scale alone produce “intelligence” or strategic clarity. Large Language Models do not become more reliable simply by absorbing more text. If the material the model ingests was previously generated by the model (or a competing model), or otherwise is poorly grounded, scaling only increases the density of error. The result is not superior insight, but hardened confidence built on weak foundations. Any society that relies on such systems risks degrading its own decision-making.

The real competition, then, is not who moves fastest, but who can scale without eroding the integrity of knowledge itself to the point where they have to scrape the mold off the cheese and wisdom is nowhere to be found.

For the technical purist, I am not going to discuss high-dimension space. I don’t need to be that precise to make the points I want to make in this essay.

Also for the purist: I know there is no ‘in’ or ‘out’ in the high-dimension space of an LLM. Again, this is about building a prior frame of reference.

As with the technicalities of AI, and for the same reasons, I am deliberately over-simplifying here.

See Tomas Mikolov, et. al. (2013) : “Efficient Estimation of Word Representations in Vector Space” and “Distributed Representations of Words and Phrases and their Compositionality.” Taken from this, researchers calculated a vector from “man” to “woman” and then applied it to “king.” The vector landed in the same basic place as “queen.” No previous “definitions” for words like man, king, woman, or queen. No “rules” from the definitions. No “programming” to implement or enforce the rules. Just raw text, statistically modeled according to how words are used. Later research suggested a detailed explanation for why. (Allen & Hospedales (2019) “Analogies Explained: Towards Understanding Word Embeddings.”)

Please forgive me for being repetitive to a ridiculous extreme. I know the difference between 3D and “high dimension space.” It just does not matter if the point is to develop a prior frame of reference, or to appreciate how computer science and philosophy intersect.

In philosophy, an a priori (Latin specialty language for “from what comes before”) is a precept that constrains how we proceed to think about a subject.

During the 2008 U.S. presidential election season, American comedian Tina Fey landed what is probably the best impersonation ever in American comedy - of Alaska governor and Vice-Presidential candidate Sarah Palin. Fey could easily have pulled off a live speaking engagement during the campaign season and fooled an entire theater. That wouldn’t have made her Sarah Palin, though, just a drop dead perfect impersonation.